A handful of entrepreneurs are out to disrupt the daily routines of workers in oil exploration and production (E&P) by applying digital technologies.

The entrepreneurs are members of a generation of digital natives who grew up expecting constant online contact and information, so their ideas are typically a version of how they expect the world to work.

RunTitle wants to cut the number of days spent in courthouses searching title records to find the owners of mineral rights by creating a national online database.

The Global Material Exchange (Gmex) is creating an online marketplace for the millions of tons of steel products now bought and sold using phones, faxes, and email.

Skynet Labs plans to replace spreadsheets and manual calculations by drillers with applications that can be used on smartphones or tablets, and ultimately with a cloud-based system offering greater computing power and the ability to collaborate.

Secure Nok is going about drilling rig security from a different angle, looking for signs of trouble by closely analyzing machine performance.

Waveseis seeks to create better seismic images of formations otherwise obscured by thick layers of salt.

They are among the 12 companies in the second class of startups nurtured by the Surge Accelerator—a 2-year-old Houston venture created to use techniques developed in the technology sector to jump-start early-stage companies in energy. About half the business plans are based on software to improve oil and gas operations.

Surge was founded on the premise that the energy industry is ripe for a digitally driven change that has transformed business sectors such as finance and manufacturing. “They (plans of Surge companies) are all focused on collecting data, managing data, analyzing data—all in real time—and providing actions on top of that,” said Kirk Coburn, managing director of Surge, who summed it up as “true real-time intelligence.”

Initially, Surge was investing only in software for energy—including alternative energy and electricity—but its investment committee has added hardware. The group includes Dynamo Micropower, which makes a simplified turbine that can be powered by wellhead gas to generate power. Water has also been added because it is so critical in this realm.

If these ideas turn into profitable enterprises, Coburn and the other Surge backers have a chance to profit from it. The accelerator gets a 6% stake in the companies in exchange for financial support, training, mentoring, and connections to potential investors and users during a 3-month program in Houston.

Of the 23 companies backed by Surge over the past 2 years, 21 are still in business, Coburn said. In the world of technology startups, failures are a given—success often comes only after many tries—and an idea that does not work often inspires another. Ariel Sella, the founder of one of the Surge startups that stopped, was inspired to create an accelerator called Azimpo in Tel Aviv, Israel, to support entrepreneurs working to help a range of industries operate more efficiently.

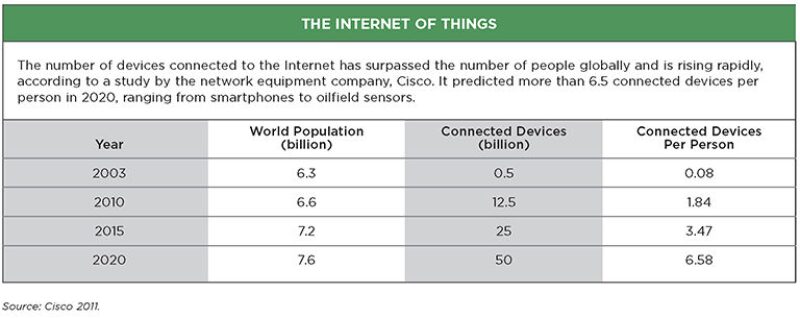

While he is not targeting the energy industry, there is a common link. Both accelerators see opportunities in the exploding number of devices connected over the Internet—many of which have sensors—known as the Internet of things.

The challenge for those picking ideas is finding ones offering the upside that comes with disrupting the status quo, but there is a limit to the pace of change. Sometimes “being early is the equivalent of being wrong,” Coburn said.

Raising Money

During Surge Day in late May, members of the class made their pitch to investors gathered in an auditorium in the House of Blues in downtown Houston. The production made full use of the lighting and sound system normally used for music shows, with short pitches playing up a problem and a solution. The lineup offered an interesting sample of the digital opportunities in E&P.

RunTitle’s Chief Executive Officer Reid Calhoon pitched his business by saying: “We are wasting our time driving out to courthouses and researching titles.” To limit the outlay, the company is creating a digital marketplace for the reports owned by oil companies and regional companies in the report business. It is raising money to hire software developers and salespeople to expand this resale market.

All these businesses are after niches that require limited capital. Compared with the enormous scale of the oil industry, the money backing the Surge startups is tiny—the amount raised by the first class of companies was hardly enough to drill and complete two shale wells.

To support the 12 ventures in Surge’s second class of startups, the program’s backers put up USD 1.2 million, with one-third of the money covering the operation and the rest supporting the companies—it pays for them to live in Houston for 3 months and to work together in an open space where each startup has a cubicle. The goal is to create a supportive environment offering useful information, advice, and inspiration through what can be a lonely process of starting a business.

Improving the Odds

Surge is modeled after similar ventures in tech centers such as California’s Silicon Valley. The goal is to improve the odds for new ventures by offering support, training, and advice from experienced mentors, some of whom are investors and many working for major oil companies. The process often leads to changes in plans, sometimes complete changes in their direction, which is known as a pivot.

Among the mentors is Gene Ennis, best known as the chief executive officer of Landmark Graphics during a rapid growth period for the innovative seismic software company that was acquired by Halliburton. He was involved in several startups and knows the odds.

“Based on data gathered in the venture capital (VC) business, out of every 10 startups backed by investors, one will be a home run,” Ennis said, adding, “It might be one in 20 depending on the economy and other things we cannot control.”

These entrepreneurs were looking for investments from venture capital firms that have become more selective. “If you look at the ones VCs out there today are doing what they are doing in a much more conservative way than 20 years ago,” Ennis said.

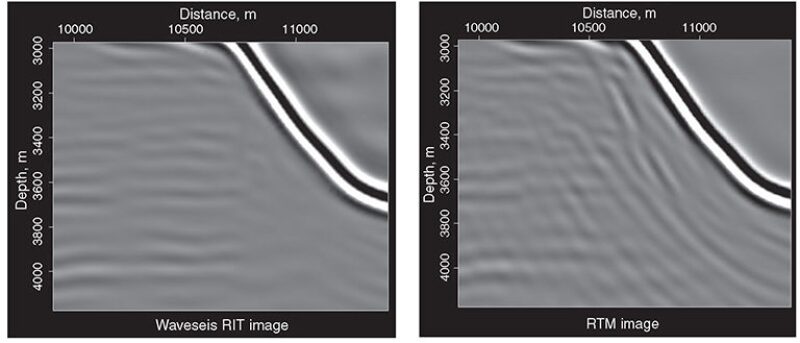

On Surge Day, the goal for nearly all the members of the class was raising money. The one exception was Waveseis. The two-person company is built on an algorithm created by Mark Roberts, a former BP research geophysicist. That formula is the basis for a program designed to create more accurate images showing oil and gas targets beneath thick salt layers.

So far, Waveseis’ business plan has required a huge investment of Roberts’ time, but not much cash. “Mark plans to use this to get into the business,” said Ennis, who is advising the venture. The goal is to use revenue from the first program to pay for a series of improved seismic processing software designed with the needs of a select group of clients in mind.

What Roberts lacks is access to the field data to demonstrate he can create more accurate images of reservoirs below salt layers. So far, the evidence is limited to images created with synthetic data sets simulating conditions found in the ground. Roberts knows from experience that they are always clearer than the real data.

Getting the data he needed to create the image and verify its accuracy was more difficult because Roberts also needed permission to show the results to potential customers. “It is always a challenge to get oil companies to show their data outside their walls,” he said.

Oil and Software

The Surge portfolio ranges from monitoring the health of drilling equipment to creating online markets.

Secure Nok’s business plan is based on a different way of sniffing out malicious software (malware). Its focus is machine performance, analyzing the data seeking early indications that a drilling rig control system has been compromised.

Most defense programs are designed to block incoming threats by identifying programs with code associated with malware. Malware creators can stay ahead of those defenses by changing the code used, with programs now able to reside unnoticed for years before attacking.

The monitoring and detection part of Secure Nok’s programs looks for trouble in a different way—by comparing its current performance with data gathered during tests of the machines, as well as performance expectations learned from on-the-job performance as observed by an artificial intelligence program.

“Basically, our solution does not look for known attack patterns and signatures, which is the common way used in existing monitoring solutions,” said Siv Hilde Houmb, chief executive officer of Secure Nok. “Our solution evaluates the machine behavior to determine whether it is ‘normal’ or potentially ‘abnormal’ based on observations during testing, which is updated in the field using artificial intelligence methods to better observe and evaluate behavior.”

This diagnostic program is at the heart of Secure Nok’s incident-handling tool that advises operators on how to handle potential problems in a way that is supposed to minimize interruptions, Houmb said.

“The drilling market is our first focus, as we have partnerships and experience in this space,” Houmb said. She said the company is collaborating with an equipment maker on pilots with a goal of building its software into the company’s equipment.

RunTitle is looking to change the way companies buy mineral rights, with an online market for title information. Based on their experience working as landmen, the company’s two founders created what they hope will be the online market for reports previously done to identify mineral rights owners.

The goal is an easy-to-use database covering all the significant unconventional oil and gas plays in the US, offering data for a fraction of the cost of hiring someone to go to a courthouse and do a title search. The reports are from oil companies and regional title databases seeking to resell old research.

As of June, the company said it had exclusive rights deals covering 15 million acres, or about 10% of its goal. While the reports are often several years old, updating those is far less work than starting from scratch.

“When 50 people have done this title search before, there is no reason for me to go back to 1830,” said Charlie Wohleber, chief operations officer for RunTitle.

Similar thinking went into the creation of the online metals exchange, known as Gmex. Jeremy Chapman said the idea for the company goes back to his time working as a metals buyer in the oil industry spending his days making one-on-one contacts with suppliers to fill orders.

Gmex’s goal is a widely used competitive online market in which approved vendors bid on orders from industrial users. The challenge is to generate enough volume, so buyers and sellers can rely on it for a wide range of orders, which will justify the fees it needs to support the business. While in the Surge program, Chapman said they worked to make it more user-friendly, inspired by the car sales website Autotrader.com.

Skynet Labs is seeking to use cloud computing and the Internet to provide people in oil and gas with simple mobile ways to analyze data, said Tim Duggan, chief executive officer of Skynet.

The first products for the company were applications used by drillers built on widely used American Petroleum Institute formulas. The products include security to ensure this work cannot be viewed by network hackers, Duggan said. To grow, he is looking at sources of more widely used industry formulas, such as widely used ones in SPE papers, which Skynet can turn into an app in a relatively short period of time.

The company is working to move beyond a single-user customer base of engineers to operators and service companies by offering a cloud-based system. Now in testing, this system will allow multiple users to log in and view each other’s work in a secure online space where access is controlled and the work is saved.

An early inspiration for Duggan was seeing how his father, a drilling engineer, would do calculations using a personal computer or paper, pencil, and a calculator. Duggan said, “The oil and gas drilling industry is drowning in Excel spreadsheets.”