On the day last February that the US Geological Survey (USGS) came out with a report saying up to 2 billion bbl of oil could be produced from shale formations on the North Slope of Alaska, a company was already planning to drill on its 500,000-acre lease.

That was a striking change at the agency where years separated the release of assessments and exploration in plays such as the Marcellus said David Houseknecht, a research geologist for the USGS and the lead author of the North Slope assessment.

The explorers and the government geologists drew on similar sources to conclude the North Slope could be a likely spot for the next US shale exploration boom.

While the USGS was working on its North Slope evaluation, geologists like Ed Duncan were looking for signs the rocks that were the source of oil that migrated over long periods into huge conventional reservoirs, such as the Prudhoe Bay, Kuparuk, and Alpine, could also be rich sources of oil.

Using what he’d learned early in his career working the North Slope and later as a consultant for companies seeking new shale plays, Duncan and his wife Karen Duncan, formed a company called Great Bear Petroleum and put in a surprise bid at the December 2010 Alaska state lease sale.

“I was stunned by the potential, with three of the most prolific oil source rocks and nobody was doing anything with them,” said Duncan, who is president and chief executive officer at Great Bear.

At the time he told the story of how he came to explore the North Slope, Duncan was in Golden, Colorado, at a Weatherford lab studying the core samples collected from Great Bear’s test wells, the Alcor and the Merak, drilled in the summer of 2012.

The wells near the gravel road that parallels the Trans-Alaska Pipeline penetrated all three source rock formations. The early evaluations were all in line with expectations but in late December he was just beginning to see the results of the tests of formations so rarely seen that a USGS geologist came out to examine them.

Duncan hopes to drill a horizontal well, fracture it, and do a production test next, but: “As much as I would love to say here is the result, let’s go ahead with a fracture-flow test, that is not the case,” he said.

“We are learning a tremendous amount every day,” Duncan said after 2 days in Golden. But critical tests on the rock properties indicating whether it could be effectively fractured would not come in until February. “My father would say there is plenty of wood to chop here,” he said.

The formations he is exploring appear to have the potential of oil production on the scale of such major US shale resources as the Bakken in North Dakota or the Eagle Ford in Texas. But the USGS assessment puts the range at from zero to 2 billion barrels, based on what is technically possible to produce using current exploration and production techniques.

While there is a high probability for large amounts of oil in the rock, what is known about the source rock is limited, and there are significant questions to answer concerning the cost and logistics of high-volume drilling in a place where there are so few rigs, workers, and roads.

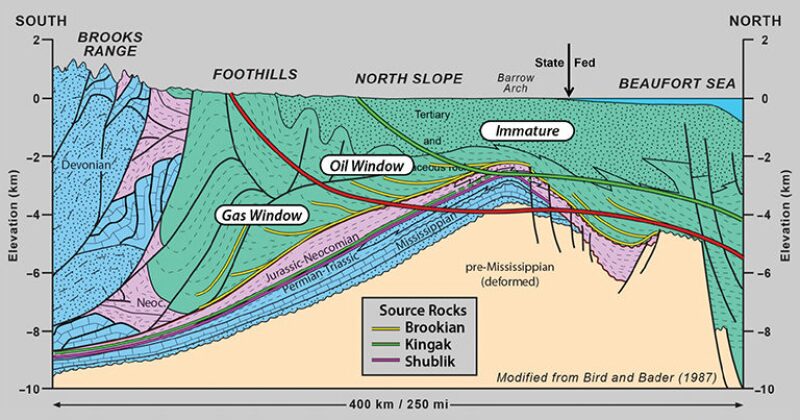

The case for the 2 billion bbl estimate, which could go higher as more is learned, is based on the productivity of the three layers of rocks that were the source of the oil for some of the largest fields ever discovered in North America. Of the three zones, which the USGS calls the Kingak, Brookian, and Shublik, the one with the highest probability of success is the Shublik.

“When you consider the assessed resource volume per unit area the Bakken is head and shoulders above everything else,” but the Shublik is not far behind based on the oil per acre, said Houseknecht, after speaking at the Arctic Technology Conference in early December.

“The big question that still remains on the North Slope is: Is shale oil economically viable?” he said. “What I can say is we made maps. We won’t know whether those maps work or not until someone drills.”

Highly Interested Parties

The soonest a production test could occur is this summer, if a rig is available in this tight market. Great Bear’s rig lease ran out at the end of 2012.

The fact Duncan could consider another summer of drilling is testament to the strategic location of Great Bear’s leases, which straddle the Dalton Highway, commonly called the haul road, which runs along the Trans-Alaska Pipeline.

During the summer thaw, areas outside the roadbed are too soft for moving and operating drilling equipment, so exploration drilling is limited to winter when ice roads allow access to remote ice pads built for drilling. If this reaches the development stage, gravel roads can be built for year-round access with state approval.

Great Bear’s exploration program is being closely followed by a select group of people.

One is Alaska State Sen. Joe Paskvan, from Fairbanks who has made promoting development of North Slope shale a personal cause because the state’s economy depends on oil production.

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline is running at less than half of its capacity, which was reduced to lower operating costs as the output from the North Slope declines after decades of production. In a state where oil revenues are both the largest source of government revenue, and the source of annual payments to its people, the level of oil in the pipeline is a vital economic indicator.

For Mohamed Abdel-Rahman, the vice president for exploration and production for Royale Energy, who convinced the management of the publicly traded company to lease 100,000 acres in the play, Great Bear’s results will be of great interest.

He and Duncan learned about the source rocks while working as geologists in Alaska for Sohio, which was later acquired by BP. In recent years, while Duncan was considering whether the three source rocks could be productive, Abdel-Rahman said he was talking to people within Royale about the potential there.

Unlike Duncan, who created a company with a single purpose in mind, Abdel-Rahman works for an E&P company that has spread its limited capital over conventional fields in several US states. Royale’s management would not approve an investment in the frontier play until Great Bear’s move at the 2010 lease sale. That proved to be a catalyst for Royale to make a similar move a year later, picking up leases to the east and west of Great Bear’s stake, including some that offered the added benefit of conventional exploration potential.

The San Diego, California, company is working on its exploration plan and will pay close attention to Great Bear’s exploration work.

“We are trying to take advantage of Ed Duncan being ahead of us in the play,” Abdel-Rahman said. He predicted that Great Bear will be successful and when it is: “You can only keep secrets there for so long in the industry.”

Good Source Material

What is known about the shale resources grew out of decades of searching for oil that led to the discovery of prolific oil fields of the North Slope.

A key source in Duncan’s research was a 2006 USGS report on the sources of oil in conventional reservoirs on the North Slope.

The 2012 USGS assessment added to past work by estimating the chance of drilling and producing oil and gas from the source rocks. It offered a mean estimate of 940 billion bbl of technically recoverable oil in the Shublik, Kingak, and Brookian formations between 7,000 and 9,000 ft depth.

While the three zones evaluated are commonly referred to as shales, Houseknecht prefers source rocks because carbonate rocks, such as limestone in the Shublik, are common.

Source rock names on the North Slope can be confusing for newcomers. What the USGS calls the Brookian includes the layers identified as the pebble shale and the Hue shale. Other names used are the HRZ or GRZ, depending on

the source.

The least known is the Kingak, which is one reason why the estimated ultimate production is expected to be low by the USGS, and the risk it will never produce is the highest of the three. The Kingak is only expected to yield from zero to 117 million bbl of oil, with a mean estimate of 28 million bbl that is technically recoverable.

The oil resource in the Shublik and Brookian is comparable, with the high end of the estimate at 928 million bbl for the Shublik and 955 million bbl of technically recoverable oil in the Brookian. The mean for each was nearly half the maximum. But on an acre-by-acre basis the Shublik is richer because its reserves are concentrated in about one-third the area as the Brookian.

The Shublik appears to offer the most potential based on its organic content—the kerogen which can produce oil or gas depending on its age and environment—and the layer’s mineral makeup that suggests it is brittle and easily fractured.

“The Shublik is rich in organic carbon, most of the kerogen is oil prone and not diluted by gas-prone kerogen, and it has the magical combination of organic-rich shale interbedded with brittle lithologies, like limestone,” Houseknecht said. “A lot of people have used the Eagle Ford as an analogy and that is fair based on the lithology.”

The research is based on what has been learned as these source rocks were penetrated while drilling conventional oil wells, but the information there is scant compared to US formations in places such as Oklahoma and Texas where so many more wells have been drilled. “There is a real lack of data over much of the area,” said Houseknecht.

When Abdel-Rahman was presenting his analysis to Royale’s board, he was asked about what had been learned from core samples from the source rock during past exploration drilling.

“I said these wells were drilled in the ‘80s. If I as a geologist decided to core shale, I would have gotten fired. You waited until you reached oil sands” to spend on collecting core samples, he said.

The USGS filled in the gaps in different ways for each formation. With the Brookian, gamma-ray logs were available to confirm the organic content. The method is based on the fact that there is a correlation between the presence of oil in shale and radioactive elements such as uranium. This approach could not be used in the other two formations due to the high level of carbonates, Houseknecht said.

The oil- and gas-prone areas of the Shublik were identified by mapping layers of rock described as transgressive facies, which in that source rock is likely to have a high organic content and hold oil and gas. Another consideration was the thickness of the transgressive facies mapped, which exceeds 200 ft in some places.

What little is known about the Kingak suggested getting the hydrocarbons out by fracturing could be a problem. It is likely to hold oil because the Kingak has been identified as the source of the oil in the Alpine Field, which was one of the largest US discoveries in the past 25 years, Houseknecht said.

But the high clay content in the Kingak could give it a “greasy” texture, which would bend rather than break if hydraulic pressure was used to try to fracture it, he said.

The first likely target for a production test is the Shublik, which is the zone assigned the highest probability of success by the USGS—95%—a bit higher than the 90% probability that oil can be technically produced from the Brookian. At the bottom is the Kingak 40%. But with so little physical evidence available, all of those numbers are subject to change.

“We are looking at the Kingak in great detail. It is a research project. We still do not know that much about it,” Duncan said. “The Kingak core we have is to my knowledge the only core in existence.”

Pushing the Economic Envelope

The USGS concluded there is an enormous amount of gas in those three rock layers as well—the range is zero to 80 Tcf of gas. But the economics for North Slope shale gas now push the likely amount down to zero because the unconventional gas is competing with lower-cost conventional wells, which cannot be sold because there is no way to deliver gas to users, and the cost of doing so would be extremely high.

Oil prices have been favorable and there’s plenty of pipeline capacity, but drilling and fracturing hundreds of wells will require importing rigs and crews on a huge scale to this remote region.

Exploration wells there cost considerably more than they would in the continental US, but Duncan said that gap could be closed if modern rigs were used to mass-produce wells. He has spoken at public hearings in Alaska about drilling and completing 200 wells a year—about 16 a month. That is not an unusual number for a single large operator in the Eagle Ford, but it exceeds the annual total some years on the North Slope, where an available rig can be hard to find.

“We need to recognize the need for new, modern equipment in the state,” Duncan said. Bringing in rigs is a challenge where the transport link is barge service when the ice allows, or trucking it up on the haul road through the Brooks Range. That route has been often featured on the reality television series, Ice Road Truckers, which highlights the perils

of the job.

Anyone making a large investment in new drilling equipment would need to consider the seasonal limits on exploration drilling, which is only done in the months when it is cold enough to build ice roads and drilling pads. That limit means many rigs remain idle during the warmer months.

Senator Paskvan said an extended road system could allow year-round drilling, but those would need to be built by producers. The state’s tax system would help cover that cost by offering a credit covering production development, as it does for exploration spending.

Roads are one of a long list of logistical challenges. The state has a list of 16 issues that will need to be addressed for developing unconventional resources there. They range from producing water for fracturing by drilling wells into an aquifer with non-potable water, to disposing of it and treating sewage from the operation. Delivering large amounts of gravel for building roads and drilling pads, sand for hydraulic fracturing, and pipe are on the list. Drilling crews would need to be hired and housed as well.

If Great Bear’s testing shows the shale can be profitably developed, the high upfront cost of widespread development would require raising an enormous sum of money for a company its size, or selling all or part of the company to someone with deeper pockets and shale production expertise.

On the plus side of the economic equation, each well site could offer up to three unconventional oil formations and perhaps other possibilities. There are indications of conventional prospects on Great Bear’s 60-sq-mile 3D seismic survey, Duncan said.

That does not represent a change in the company’s plan to go after oil in shale, but it can increase the ultimate production per well improving the case for unconventional develop-

ment there.

For Further Reading

- A Window Into Alaska’s Unconventional Frontier:http://energy.usgs.gov/Portals/0/Rooms/audiovisual/AK_ShaleResourcesRelease_pdfweb_mar2012.pdf

- David W. Houseknecht, William A. Rouse, and Christopher P. Garriby, US Geological Survey 2012. Arctic Alaska Shale-Oil and Shale-Gas Resource Potential. Paper OTC 23796 presented at the OTC Arctic Technology Conference, Houston, Texas, 3–5 December, 2012.

- US Geological Service Assessment of North Slope Source Rocks:http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2012/3013/