Those who track drilling and fracturing equipment are apt to mention zombies. That is the living-dead machinery still counted as available to work, but more likely now to be used for spare parts or scrapped.

In both those equipment markets, one-quarter or more of capacity is expected to disappear over time, but it is a slow-moving sort of destruction with an uncertain outcome.

Richard Spears, vice president of Spears & Associates, sees fracturing trucks massed at a service company repair facility in his hometown of Tulsa, but no one ever seems to be working on them.

“There has never been a time when the fleet has not been maintained. Based on our research, capacity falls by 5 million horsepower through the bottom of the market in the summer of 2016,” said Spears, who works for a company tracking the fracturing service business.

That represents about one-quarter of the capacity of the fracturing business where the total horsepower indicates how much water and sand can be pumped into a well to fracture the rock.

Offshore, there is an even bigger glut of floating drilling equipment. Many of those vessels are classified by their owners as stacked, which normally would mean they are being preserved for future use. Analysts predict, however, that about one-third of the more than 300 of them in existence will never return to service, even if oil prices rise.

“When the oil price recovers somewhat, perhaps to the USD 60–70/bbl, which we consider a more viable long-term oil price, we believe there is a market for 200-plus rigs in total, meaning around 100 in the traditional mid- to more shallow water depth, and around 100 rigs on the deepwater side,” said Knut Erik Løvstad, an analyst following oil services for Fondsfinans. “That means that roughly 100 rigs have to be scrapped.”

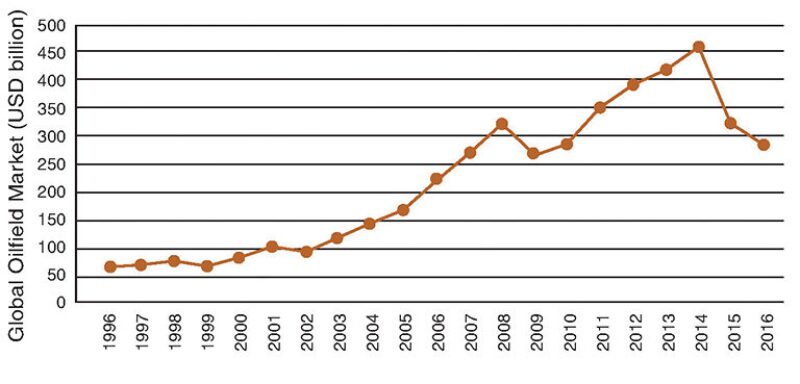

There is an oversupply of a wide range of onshore and offshore equipment, from drilling rigs to construction vessels, where the equipment built when oil was at USD 100/bbl far exceeds the likely future demand.

New equipment is still arriving in some sectors. For example, the building boom that doubled the fleet of subsea construction vessels between 2007 and 2014 is expected to increase the fleet by 8% in 2016, at a time when there are widespread project delays and cancellations.

Fracturing Capacity

The actual amount of onshore fracturing capacity lost requires an educated guess about how this process will play out in the isolated places where idle equipment is parked, and the willingness of owners to maintain it. “Where the 5 million (horsepower) goes is the question. Some of it cannot be brought back. It has been removed physically,” Spears said.

Companies in the pressure pumping business are being squeezed so hard that as equipment wears out, idle units are cannibalized for parts. While these units could be returned to service by replacing the missing and broken parts, higher day rates would be needed to justify the cost of that work.

That would require demand for more drilling and fracturing, which is not likely in the US unconventional business for some time. When the market improves, a sharp rebound is not expected. The industry has shown it can get significantly more oil per well drilled by focusing on the best rock. Increased productivity is likely to limit demand for drilling and completion services when the market improves.

Spears sees a recovery in the oil business beginning late this year, but a significant rebound in day rates for completion equipment is not likely occur before late 2017.

Deepwater Rigs

Offshore, many of the rigs facing retirement are old only in comparison to the ones that were a product of the building boom in rigs and workboats since 2010. More efficient onshore and offshore new equipment will likely push older, less efficient machinery out of service because the cost of upgrading it is too high, Løvstad said.

Although many of the older rigs are counted stacked for future use, “we do not believe that these rigs will be coming back to the market,” he said. The biggest losses will be mid-water rigs—floaters built for water depths from 500 to 3,000 ft. Jobs in water deeper than 1,500 ft will generally be done by newer deepwater rigs, he said.

Owners of the living-dead rigs have little reason to scrap them soon because steel prices are down, reducing the value of the scrap, and removing them from the fleet may trigger repayment of loans secured by the equipment, Løvstad said.

“We have assumed that it will take a couple of years to clean out the excess supply, so we expect the poor market in terms of the supply/demand balance for rigs to last through 2017, with a potential recovery in day rates in 2018–19,” he said.