If it is a truism that the nations of the developing world are engaged in the process of developing, it is also clear that, for a variety of reasons, not all nations experience the process at the same rate. In the case of Angola—the populous southern African republic described in some quarters as a dynamic, emerging powerhouse, and in others as a would-be success story stymied by cronyism—the oil industry waits to see whether the effect of recent political shifts will change the economic and social course that the nation has charted in its often-tumultuous 42 years of independence.

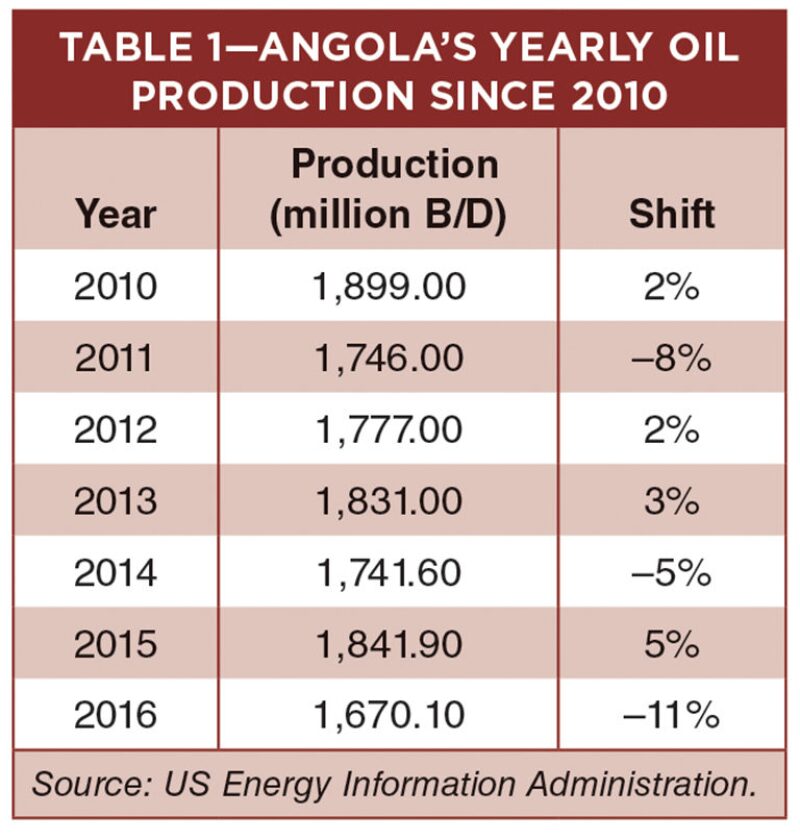

The waters off the nation’s Atlantic coast hold enormous exploration and production potential, a fact that has allowed Angola to compete with heavyweight Nigeria as the continent’s top oil producer, even surpassing the Federal Republic for several months in late 2016. After years of working to impress upon the rest of the world that it was prepared to take on a major role in the continent’s future, Angola joined the Organization of the Petroleum-Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 2007. Its proven crude reserves stand at 9.5 billion barrels (at least 1–2 billion more barrels may also rest in its presalt blocks), with another 308 billion cubic meters of natural gas reserves. At its peak in early 2010, its crude oil production reached over 2 million B/D (as of June 2017, its production stood at 1.66 million B/D after the early-2017 OPEC effort to cut production, while crude oil exports reached 1.67 million B/D). Table 1 provides Angola’s oil production in recent years.

Angola is the second-largest African supplier of oil to China, and is a top-10 global producer of vented and flared natural gas. But Angola has, naturally, been subject to the same effects of low oil prices and market instability that have wrought recent havoc on all oil-based economies, especially in light of the fact that Angola’s production is highly dependent upon cost-intensive deepwater production. As the price crash settled into its deepest ebb in 2016, the influx of foreign money from its oil exports dropped a staggering 55%.

Its famously expensive capital Luanda continues to erupt into towering walls of glass and the cranes that hoist them, but skeptics believe that Angola’s growth may be too hollow and one-dimensional to project long-term economic growth. The question now is whether a recent change in leadership, in which longtime President José Eduardo dos Santos stepped down after legislative elections, means a genuine onset of economic diversification and social development for the nation’s 28 million people, and what such a transformation might mean for the industry in Africa.

Angolan oil was first exploited onshore in the 1950s near the capital, but beginning in the late 1960s, major offshore discoveries began to drive heavy multinational investment. Such producers as Chevron, BP, Total, and Eni are involved in operations all along the northern half of Angola’s coastline and offshore Cabinda, the 2,800-square-mile exclave separated from the rest of Angola by a strand of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Before the recent drop in oil prices, Angola thrived as petrodollars drew southern Africans and multinational-company personnel to Luanda by the hundreds of thousands; Luanda enjoyed the highest growth rate of any city on the continent by 2015, by which time it had gained notoriety as the world’s most expensive city for expats. Despite the appearances of growth, analysts both outside Angola and within its state oil organization, the Sonangol Group, recognized the need for diversification in a nation whose second economic mainstays were diamonds and agriculture, both sectors long atrophied by the ravages of the civil war. The Angolan government has announced efforts to prioritize diversification in a drive reminiscent of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. The fact remains, however, that for the vast majority of Angolans, the promise of development has remained limited to the streets and high-rises of the capital; estimates place the number of Angolans living below the poverty line between 36 and 68% of the total population.

In the political sphere, it is the government and its decades of immovability that have made investment in Angolan operations a complex proposition for multinationals. Dos Santos, a leader of the war of independence against Portuguese colonial rule in the 1970s, guided his Marxist People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) to victory over both colonial forces and, then, a host of domestic and foreign opponents in the 25-year civil war that followed. Final victory in that conflict in 2002 allowed dos Santos to officially position the MPLA as a political rather than a military force, and set the stage for last August’s unprecedented legislative elections, in which dos Santos agreed to step down to make way for a new state leader. While the results surprised few—the victor was the MPLA’s João Lourenço, dos Santos’ chosen successor—the MPLA posited the results as a genuine mandate of rule among Angolans, while opposition parties charged the regime with vote-tampering. As skeptical as some are of the scope of change represented by the election, it nevertheless represents an example of organized leadership change to which many observers attach some expectation of diversified, wide-ranging development.

Although Angola hopes to expand a number of other economic sectors in order to make diversification a reality, these efforts have thus far been challenged. Recent efforts to fund major agricultural projects have been hampered by an underdeveloped infrastructure, despite a concerted campaign to modernize its railway system, and challenges posed by nonperforming loans issued by the national development bank. Its economic apparatus therefore remains oriented firmly toward oil, with the national Sonangol. The national oilfield fabrication company, Sonamet, is a joint venture between Sonangol and several multinational shareholders. Based in Lobito Bay south of the capital, Sonangol fabricates the equipment and facilities needed for the many major offshore fields currently in production (including Dalia, Girassol, Hungo, Chocalho, and Acacia, among several operational areas). The national entities have increasingly focused on issues of health, safety, and social responsibility along with operators and service companies of all kinds in recent years, but resources provided to allow these oil industry reorientations only pose further obstacles to diversification.

The Atlantic waters are simply too laden with the promise of a stable and economically viable prosperity for Angola for its many investors to reverse course, although some have wholly (Vaalco) or partially (BP) sold off Angolan assets in the past 2 years. To complicate matters, US operator Cobalt International Energy is currently locked in a legal battle with Sonangol over licensing extension guidelines. Nevertheless, dozens of rigs and drillships ply and dot the waters of the republic’s 50 offshore blocks. But as the nation prepares to welcome its first new occupant in the Presidential office since independence, observers worldwide hope that, for a variety of reasons, political change might be a prompt for a long-awaited development that will benefit both Angola’s people—and the many investors whose success is bound up in their own.