While the collapse in oil price is reshaping opinions about the North American shale revolution and the outlook for oil producers, natural gas producers in the United States are in a somewhat different position. They have contended with low prices since late 2008 and yet remain in a domestic market with substantial long-term growth potential while soon anticipating access to higher-priced global export markets as low-cost producers.

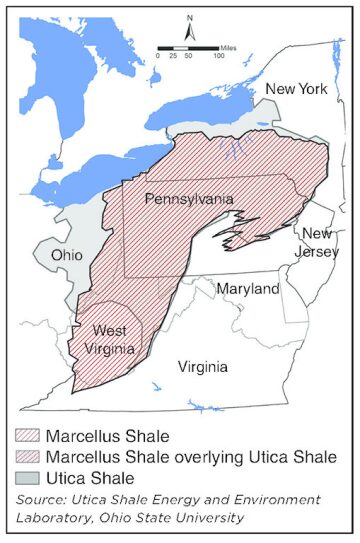

No producing area is more invested in the future of US natural gas than the Marcellus Shale that stretches across much of the Appalachian Basin, with development activities concentrated in Pennsylvania and West Virginia. The Marcellus produces approximately 20% of US gas supplies. And beneath the formation lies the highly prospective Utica Shale, in which drilling and production, especially in eastern Ohio, are getting under way.

The near-term outlook is anything but rosy at current natural gas prices ranging below USD 3/Mcf at the wellhead. However, the producers generally have plenty of experience with low prices. With a constant focus on technological innovation and increased efficiency, and the continuing expansion of the midstream network to create more marketing options, the gas industry in the Marcellus and Utica is laying the groundwork for a better future for many decades to come.

“I think we’re just really in the beginning of realizing how much potential is actually in the Marcellus and the Utica,” said Jeffrey Daniels, director of the Utica Shale Energy and Environment Laboratory at Ohio State University. Daniels is a professor of Earth sciences at the university and a member of the Ohio Oil & Gas Commission.

According to the most recent estimate by the US Energy Information Administration, the Marcellus holds 354 Tcf of proved gas reserves. However, technically recoverable gas reserves, an assessment that does not consider gas prices, have been estimated at 480 Tcf by Terry Engelder, a geosciences professor at Pennsylvania State University.

Far fewer wells have been drilled in the Utica. The US Geological Survey in 2012 estimated technically recoverable gas reserves at 38 Tcf. But this year, an industry-financed research study coordinated by West Virginia University and involving experts from the industry, academia, and government raised that calculation by a factor of 20 to 782 Tcf.

At the IHS CERAWeek conference in Houston this year, Ed Kelly, vice president of Americas Gas and Power Consulting at IHS, introduced a session on Marcellus and Utica gas by noting that estimated production from the Marcellus, averaging 16 Bcf/D this year, would exceed 20 Bcf/D in 2020 and potentially surpass 30 Bcf/D between 2030 and 2035.

IHS analysts have projected that more than 211 Tcf of natural gas resources will be available in the Marcellus/Utica area at a break-even price of USD 3.25/Mcf or less, Kelly said. Little wonder that the session title described the Marcellus and Utica as “the elephant in the room.”

‘Kind of Limitless’

“I think the potential of the Marcellus is kind of limitless,” said Kyle Mork, president of Energy Corporation of America (ECA), which has actively operated in the region for years and is focused on drilling and production in West Virginia and southwestern Pennsylvania.

“We believe firmly that the Marcellus is the best dry gas basin in the country, meaning the lowest cost, particularly in the core areas. In my opinion, we are still in the very early stages of the overall Marcellus life cycle,” he said.

The two geological sweet spots for the drilling and development of the Marcellus are in the northeastern and southwestern portions of Pennsylvania, extending into northern West Virginia.

“I don’t know if we’re going to find brand-new sweet spots, but I think what’s going to happen is that the productive area of the Marcellus will certainly extend along the whole diagonal from northeast to southwest in Pennsylvania and pretty far down into West Virginia,” Mork said. “And I think people will develop those areas more fully as prices start to come up.”

As such activity increases, Mork believes that the industry will continue to learn and optimize the appropriate drilling and completion techniques for the new wells. “I do think we will get continuously improving results in all of the new areas just because we will experiment and do what the oil and gas business always does: figure out how to make things better,” he said.

As for the Utica, ECA has tested the formation and is encouraged, although not yet developing acreage there. “You’ve seen a lot of big results announced in the dry gas Utica in northern West Virginia and far western Pennsylvania,” Mork said. “And we have lots of acreage through that swath from central West Virginia through central Pennsylvania. So we’re really encouraged, but hanging back a little bit to see more early industry results because we are fortunate enough to have acreage that is largely held by production. But we think the Utica is going to be a very, very big resource.”

Southwestern Energy has been involved in the northeastern Pennsylvania portion of the Marcellus play since 2007. The company stepped up its activity late last year with a major acquisition of production and development properties (more than 400,000 net acres) in West Virginia and southwestern Pennsylvania from Chesapeake and asset interests in the same area from Statoil. The acquisitions also included Utica and Upper Devonian shale acreage.

In its Northeast Appalachia Division, which covers northeastern Pennsylvania, Southwestern was producing a gross 1.2 Bcf/D of gas at midyear from 367 operated horizontal wells.

The company drills its wells by using a small spudder rig, which drills underbalanced, on the vertical section and a larger re-entry rig, which drills overbalanced, on the horizontal section. The current drilling program keeps three re-entry rigs in regular use.

Southwestern estimates that it will drill and complete between 88 and 92 horizontal wells in this portion of the Marcellus this year, said Jack Bergeron, senior vice president for Northeast Appalachia. “The company has a good, firm transportation position in northeast Pennsylvania,” he said. “We are able to invest and make money at even today’s gas prices because of our transportation and the low operating cost structure we’ve created.”

In the Southwest Appalachia Division, which comprises the newly acquired northern West Virginia and southwestern Pennsylvania acreage, the company was producing a gross 650 MMcfe/D of gas and liquids at midyear. The drilling program called for 50 to 55 new horizontal wells this year.

Three company-owned rotary steerable rigs are used for drilling. Because of the mountainous terrain, the use of spudder rigs is impractical. However, as in northeastern Pennsylvania, vertical hole sections are drilled underbalanced. The wells drilled and completed by Southwestern have shown significantly improved early results compared with the inherited offset wells, the company reports.

Most of the division’s wells in the new area to date are wet gas wells for which post-production gas processing is required. With the downward price pressure on natural gas liquids (NGLs), reflecting the decline in oil prices, “we’re expanding the flexibility to move toward more dry gas drilling in the Marcellus and the Utica,” said Paul Geiger, senior vice president for Southwest Appalachia. “We are spudding our first Utica well and plan to bring it on line late this year.”

With some improvement in gas and/or NGL prices, the company could ramp up yearly drilling in the division to 70 wells and eventually 100 to 200 wells, Geiger said.

Technology Innovation

An emphasis on technology innovation to increase efficiency has been crucial to the success of Marcellus-area operations.

ECA has taken measures such as installing water handling systems, using bi-fuel rigs and fracking units, and drilling largely from multiwell pads, many of which have eight or nine wells. “All of these things result in lower costs or improved speed and efficiency within our operations,” Mork said.

He also cites the industry’s tremendous progress in improving well completions. “A lot of operators have gone to reduced cluster spacing using smaller, tighter stages on their completions,” Mork said. “And there has been significant success in increasing the amount of sand that gets pumped.”

The sand factor, the increased proppant pumped per foot, has been a big driver of well performance for Southwestern in both of its Marcellus-area operating divisions.

“We have been able to increase the concentration of proppant by up to 65%, compared with what was done with wells in the area before we acquired our acreage,” Geiger said.

Taking lessons learned in its successful Fayetteville Shale operations in Arkansas, the company has also fine-tuned its ability to direct lateral drilling.

“There is a particular bench in the Upper Marcellus that we would like to stay within, which varies from 10 to 20 ft thick across our acreage,” Geiger said. “We have been able to land our laterals properly in there and maintain them in that tight window even out to a record lateral that we just drilled over 12,000 ft, which stayed 99% in the target zone.

“The two things that have enabled us to do that are the use of azimuthal gamma ray measurement-while-drilling technology, which lets our geosteerers know exactly where they are and the rotary steerable technology.”

Although the company does not use rotary steerable rigs in northeastern Pennsylvania, it uses azimuthal gamma ray technology to maintain tight lateral control.

Another technology that has aided Southwestern in all its operating areas is the walking rig. The rigs are able to move themselves hydraulically from one location to another on a pad with pipe racked in the derrick, thus eliminating the need to rig down and lay pipe out of the derrick.

Southwestern is also making use of water recycling technology to conserve the water used in field operations. It is part of a broader companywide commitment to become neutral in freshwater use within operations by next year. For every gallon used, the goal is to replenish or offset the equivalent volume through conservation or technology innovation. Finding ways to reduce water needs and further protect water sources are also part of the strategy.

Stacked Pay Zones

Part of the long-term potential of the Marcellus and Utica plays lies in the opportunity they provide to exploit stacked pay zones that could include other shales and, in some cases, conventional porous hydrocarbon-bearing rock.

Oil and gas have been produced in the geographic region of the Marcellus and Utica basins for considerably more than 100 years.

“You have somewhere between 500,000 and 600,000 wells that have been drilled in either West Virginia, Pennsylvania, or Ohio,” Daniels of Ohio State University said. “So we have some pretty good tests of a number of shallow zones, and there are additional shales that we now have the technology to drill and produce.

“Horizontal drilling, in my view, is the real game changer because of the ability we now have to connect laterally with pay zones and the opportunity to do so in multiple pays that are produced from the same well. That also increases rig productivity. In addition to the potential to produce various shales, we may be able to get more out of—or even reopen—some conventional fields.”

Expanding Midstream Options

While it is common to speak of a low price environment for natural gas, it is somewhat misleading because it suggests that all producers face approximately the same wellhead price. That is not the case, and that fact shows the importance of building additional midstream infrastructure in the Marcellus and Utica areas, including pipelines and processing facilities. While producers in areas with good market connections may receive a gas price of USD 3/Mcf, some producers in isolated, poorly connected areas have recently seen prices closer to USD 1/Mcf.

The need for new midstream facilities has become critical as Marcellus-area gas production has rapidly expanded over the past few years. The shale revolution, especially the rise of the Marcellus play and now that of the Utica, is changing the logistics of the domestic natural gas industry. A region that once brought in gas from the South and the Gulf Coast now produces so much that it must look for other markets after meeting the needs of its own area and the Northeast.

Marcellus and Utica gas is now moving into the South and the Midwest, some of it through pipelines in which flows have been reversed. The eastern section of the Rockies Express Pipeline, for example, was recently reversed to enable Utica gas to flow from eastern Ohio to central Illinois, thereby providing access to Chicago and other markets.

Several other outbound pipeline projects have been or will be completed this year, and at least 12 more are slated to come on stream between 2016 and 2018. The new lines will connect to Southern, Gulf Coast, Midwestern, Canadian, and Northeastern markets. Nonetheless, IHS has projected that midstream bottlenecks will constrain the growth of Marcellus and Utica production through 2025.

Another potential constraint is wet gas processing. Southwestern, which produces a lot of wet gas in West Virginia and southwestern Pennsylvania, has available processing. As it envisions future production growth, ensuring adequate processing capacity “just requires proper planning of our business and good, solid integration there with the midstream companies,” Geiger said.

Possible Industrial Growth

As pipelines are built to carry gas out of the Marcellus and Utica, Daniels believes it is also important to realize additional opportunities in the local area. “It is critical that we get our own infrastructure in place and develop our own local markets so that we can utilize the resource more completely,” he said.

Mork echoed the same sentiment. “We would love to see in the future some more industrial demand in projects right here in Appalachia,” he said. “That would be fantastic.”

Low gas prices could stimulate such demand and attract chemical and manufacturing plants, which has already happened in various US locations as a result of the shale gas transformation.

Many eyes are on Thai chemical producer TPP Global, which has proposed building a multibillion-dollar ethane cracker in Belmont County, Ohio. The project, if it goes ahead, would take at least 4½ years to build. Shell is also considering building an ethane cracker in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, although a final decision has not been made. A third proposed ethane cracker project in Parkersburg, West Virginia, was recently put on hold by its Brazilian investors.

LNG Exports

Until now, the main growth factor in the domestic gas market has come from fuel switching in the utility power sector. However, a milestone is imminent for the US gas industry as liquefied natural gas (LNG) export operations are set to begin at Cheniere Energy’s Sabine Pass liquefaction terminal on the Louisiana coast at the end of the year.

For the first time, domestic gas producers will have access to global markets through gas liquefaction and LNG tanker transport. The low-cost position of US producers, particularly in the Marcellus area, should be a competitive advantage in global markets. Four more LNG export terminals are slated to come on stream by 2018.

The advent of LNG export operations is expected to support US natural gas prices and lend stabilization to a market that heretofore has fluctuated strongly on a seasonal basis.

It is less likely that the Marcellus and Utica gas will initially be physically exported from the Gulf Coast than that it will flow into Southern and Gulf markets to replace gas that is exported.

“Whether Marcellus gas molecules make it to the LNG terminal isn’t really the issue,” Mork said. “If the Gulf Coast region, for example, imports Marcellus gas to make up for export volumes, it works just as well to stabilize prices.”

Four of the five planned terminals are on the Gulf Coast. The other, Cove Point, is on Chesapeake Bay in Maryland and will be ideally suited to receive Marcellus and Utica gas when it opens in 2017.

“Depending on who’s doing the estimate, there should be between 5 Bcf/D and 10 Bcf/D of gas takeaway from LNG export demand over the next 5 years,” Geiger said. “That’s a phenomenal addition to demand. It is an exciting time for natural gas. It is becoming more nearly a globalized commodity, similar to oil. That’s nice to see.”

Even a smaller increase in demand of 2 Bcf/D to 3 Bcf/D would have “a positive impact on natural gas prices,” said Bergeron of Southwestern.

Looking ahead, Mork is hopeful of seeing light at the end of the tunnel for the US gas industry.

“All of us, including ECA, are working to fight through this period of low prices. But as an industry and as a company, it’s something we’ve done for better or worse many times. And so we are really looking to the upside as we exit this. And hopefully in the next year or two, we start seeing prices get back to a level that supports long-term development in the US,” he said.